What Piece of Art That Mary Cassatt Created Best Fit the Theme of the Gilded Age

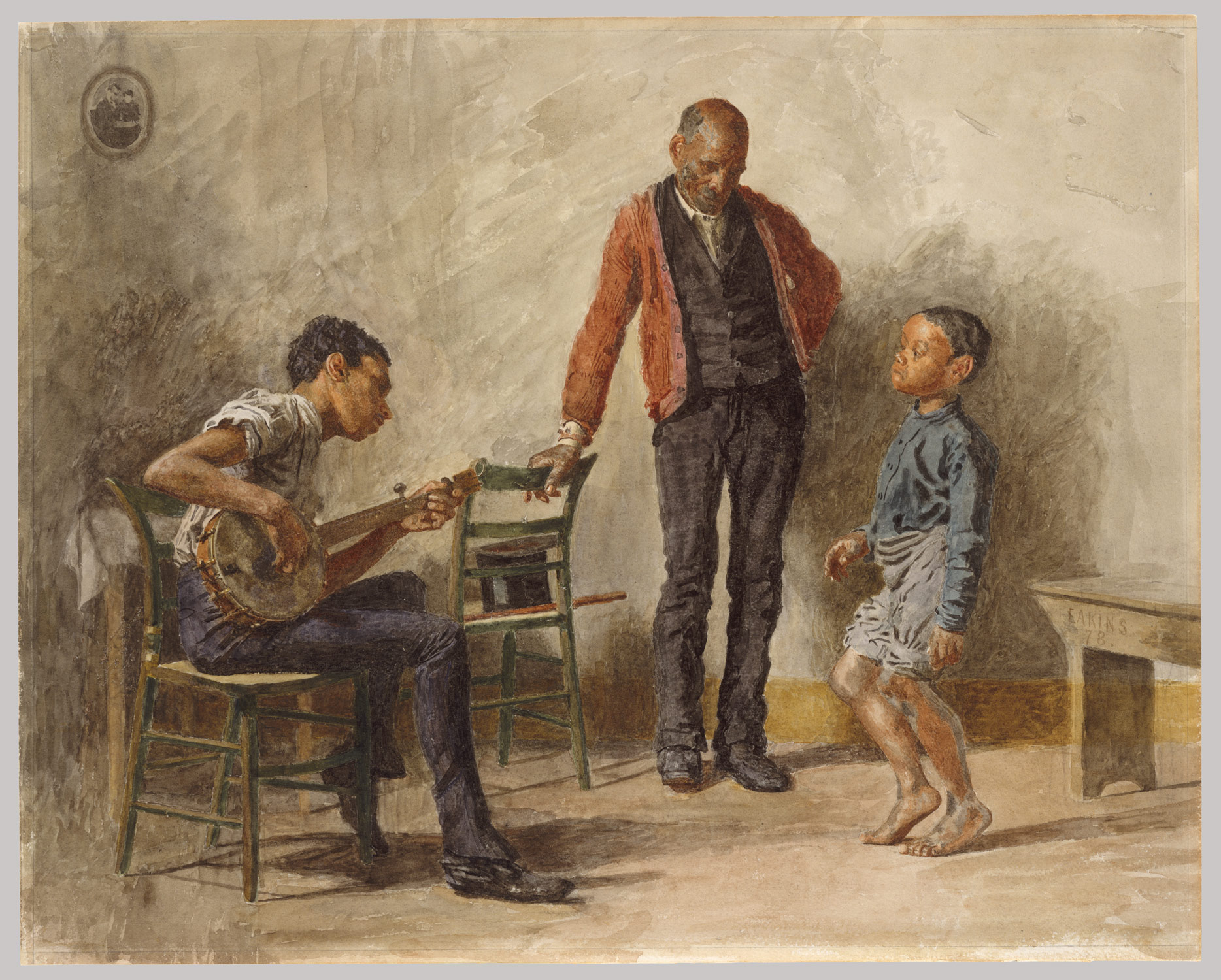

Thomas Eakins, The Dancing Lesson. 1878

"Gilded Age Drawings at The Met" is a curious attic cleaning of an exhibition. It includes the seldom seen Thomas Eakins 1878 watercolor The Dancing Lesson,featured on the testify's advertising. The painting is non an obvious choice to exemplify the Gilt Historic period, and yet, in its reproduction, it is given an importance that is otherwise left unexplained. The exhibition includes a hodgepodge of other work, some of it by lesser lights, and lacks accompanying textile about the relationship between art and era. Perhaps more than explicit commentary would take run the take a chance of offending the patron form upon whose riches the Met always has depended. The Walton Family Foundation funded this exhibition, an irony too large to remark upon except to confirm in Jamesian sotto voce that, aye, Walmart supplied the fortune. Iii of the paintings shown are intended bequests.

Thomas Eakins, The Pathetic Song, 1881.

Lush portraits by Louis Comfort Tiffany, John Vocalizer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt reinforce our dutiful impressions of the undeniable artful pleasures of material wealth as well as the dreamy sadness leisure tin can bring, especially within the domestic sphere. A drawing of a woman done in silverpoint past Thomas Wilmer Dewing has a timeless quality, amplified past the apply of an antique artistic technique. In that location likewise is the seductive suggestion that the past can be bought or had—if only one has money or sensibility enough. Eakins himself often painted and photographed women in historical wearing apparel and was every bit capable as any artist at getting lost in the luxurious folds of a fine damask or watered silk. We can see that in The Pathetic Vocal (1881), another Eakins watercolor included in the exhibition. The viewer can hear the rustle of the singer's dress as well equally the purity of her vocalism. As heard are the pianist's maniacal focus (Eakins'due south wife, Susan, was the model) and the cellist's perchance less achieved accompaniment—isn't he merely a quarter beat off tempo? The homey setting reinforces the tame and unthreatening autonomous platonic that truthful art can be created anywhere, fifty-fifty in the forepart parlor.

It is Eakins's earlier, advisedly worked watercolor, originally titled Study of Negroes, that suggests the more revolutionary thought that art belongs likewise to the dispossessed—that it is, perhaps, the get-go fruit of freedom. This sheet also depicts a group of three: a sturdy male child of at most eight years old dancing, a slender immature human being playing the banjo, and, in the heart, a human as wiry as a child but old enough to be their gramps. The clothing is once more there to exist touched, the music to be heard. The child wears the rough bluish and gray homespun attire of a laborer, his pants rolled to the articulatio genus to reveal his dancing legs; the young homo is clad in a make clean but somehow aspirational white shirt and less laundered black trousers; the old man supplies the pizazz with his frayed orangish jacket worn over a rusty black adjust, top hat and cane resting on a chair at his side. The boy looks to the banjo player, mayhap for guidance; the banjo histrion stares out as if into the music itself; and the older human being scrutinizes the male child, his human foot lifted as if moving to the beat or perhaps to demonstrate a pace. Theirs is a circle of intent: the music, the dance, the male child initiated into their mysteries.

Eakins himself, though, completes the circle. Ghost, witness, audience, fellow creative person, he faces the old man and suggests a mirror: one artist tin't exist without the other. The iconoclastic Eakins may well take seen race every bit irrelevant to serious creative intent, although The Dancing Lesson brought him 1 of the only prizes in his career, suggesting information technology probably was seen as a conventional piece of work of "local color." More than telling, perhaps, is that Eakins soon after took on as a pupil Henry Ossawa Tanner, a young African American painter who later would study in Paris with Gérôme, Eakins's very own instructor. (A minor work of Tanner's is included in the exhibition.)

Ii other figures in the watercolor serve to reinforce the sense of an artistic intent that is ultimately destructive rather than sentimental. Floating in the upper left-mitt corner on an otherwise bare wall is a small oval-framed portrait of a seated Abraham Lincoln looking downwards at a large volume, nearly certainly an album, while his youngest son, Tad, looks over his shoulder. The original photograph of this moving scene was taken in Matthew Brady's studio by Anthony Berger; the prototype was widely disseminated subsequently Lincoln's assassination when an engraving of it appeared on the cover of Harper's Weekly. Eakins'southward rendering of it in The Dancing Lesson is no more than a rough sketch, but the knowing viewer will supply in her mind the necessary item and imagine the president at once distracted and benevolent. Glasses slipping down his nose, Lincoln folds the boy into his contemplation of whatever he is looking at, perhaps one of Brady'south Ceremonious State of war photographs. So, too, the painting's architecture seems to suggest, does the president concord the people he has freed, all the same tenuously, in his immortal glance.

Peradventure more than any other work in this adulterate exhibition, The Dancing Lesson speaks to the double helix of our by and present gilded ages. The contemporary viewer knows the dead president has not ensured the freedom of those he emancipated; only federal enforcement of the Constitution and its "freedom amendments" could do that. Eakins's child dancer with his rough oversized hands and workman's clothes reminds usa that his benevolent fathers, political and creative, may be powerless to save his labor from being turned to another human being'south profit. Then, as now, voting rights were contested and concise, nativist leanings were ignited and fanned, and, behind the rhetorical smoke, wealth flowed into the hands of a very few. The reign of a wise fatherlike president may take felt no more real than a faded image upon a wall.

"Gilt Age Drawings at the Met" may be more a curiosity than an event; it seems a weak moment for an institution that has educated both the brainy and the uninitiated for so many years. As our great museums struggle to hold onto their collections, foster scholarship, and bring in wider audiences, we more ever need exhibitions that speak directly to the contradictions of our historic period—and non merely effectually them.

Cynthia Payne lives in Brooklyn, New York, and is at work on a novel.

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/12/06/reading-lines-gilded-age-drawings-met/

Post a Comment for "What Piece of Art That Mary Cassatt Created Best Fit the Theme of the Gilded Age"